An Academic Publishers’ GO FAIR Implementation Network (APIN)

by Jan Velterop and Erik Schultes

Information Services & Use, Vol. 40, Iss. 4, pp. 333–341

Communication of scientific research results is one of the pillars on which scientific progress stands. Traditionally, the published (narrative) literature was the main material from which to construct this pillar. It used to be so that data were supplementary to published articles, but in the last decades this relation has undergone an inversion, where these articles have increasingly become supplementary to the core research results, the data, as they describe the latter’s interpretation, provenance, and significance. Under such an inversion, we might start to refer to “data publication”, with “supplementary article”. An article should be seen to belong to the set of "rich provenance metadata" (although itself not machine readable, but enabling humans to determine actual “reusability” and “fitness for purpose”.

Furthermore, data repositories are playing an increasingly important role in the scientific communication and discovery process, as data availability and reusability becomes a crucial element in science’s efficiency and efficacy. The old method, which relied on “data are available upon request” (or even on “all data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request”) is not fit for purpose any longer, even when, or rather, if, data were easily available and usable that way. More and more science is also reliant on data sets that are either too large and complex to simply being made available by request, reasonable or not, from the authors following idiosyncratic methods of exchange.

In many disciplines, such as medical and psychological sciences, data are often too privacy-sensitive to be “shared” in the classical sense. They need to be anonymized, and even then, levels of trust necessary to guarantee privacy cannot always be achieved. One solution is that data are not shared by means of making them available in the traditional way, but instead, by means of making it possible to analyze data by “visiting” them in their privacy-secure silos. A good example is the Personal Health Train: The key concept here is to bring algorithms to the data where they happen to be, rather than bringing all data to a central place. The algorithms just “visit” the data, as it were, which means that no data need to be duplicated or downloaded to another location. The Personal Health Train is designed to give controlled access to heterogeneous data sources, while ensuring privacy protection and maximum engagement of individual patients, citizens, and other entities with a strong interest in the protection of data privacy. The data train concept is a generic one and is clear that it can also be applied in areas other than health sciences. For the concept to work, data need to be FAIR. FAIR has a distinctive and precise meaning in this context. It stands for data and services that are Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable by machines.

Metadata

In the new models supporting FAIR data publications, metadata is key. The most important role of publishers and preprint platforms is to ensure that detailed, domain-specific, and machine-actionable metadata are provided with all publications, including text, datasets, tabular material, and images. In other words, with all ‘research objects’ that they publish. These metadata need to comply with standards that are relevant for the domains and disciplines involved. And they need to be properly applied drawing on the controlled vocabularies created by or in close consultation with the practicing domain experts. Some of the metadata components required are already (almost) universally used, such as digital object identifiers (DOIs), although not in all cases in a way that makes them useful for machine-reading. Often enough, a DOI links to a landing page or an abstract, designed to be seen by humans, where the human eye and finger is relied upon to perform the final link through to the object itself, e.g. a PDF. Clearly, that approach is not satisfactory for machine analysis of larger amounts of data and information.

Given the information and data-density of the text in articles, it makes sense to convert assertions into semantically-rich, machine-actionable objects as well, according to the Resource Description Framework (RDF), a family of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) specifications. Where possible, assertions that leverage domain-specific vocabularies and RDF markup could be presented as semantic triples along with their appropriate metadata (“nanopublications”). If all is well, the assertions and claims mentioned in an article’s abstract should capture the gist of the article (at least to the author’s satisfaction), but also tabular data could be treated in this way. The result of the above should be a FAIR Digital Object (FDO), a digital “twin” of the originally submitted research object. It is not suggested that the onus of doing all this should be exclusively on the shoulders of publishers, but instead, should be a collaboration of publishers and (prospective) authors and increasingly, their data stewards.

Publishers would provide some of the appropriate tools, and where necessary train (or constrain), authors to indicate what the significant assertions and claims in their articles are. Examples of useful RDF metadata tools that make FAIR publication easy (or at least easier) are available from the Center for Expanded Data Annotation and Retrieval (CEDAR) and the BioPortal repository with more than 800 controlled vocabularies, many from special domains. Increasingly CEDAR has been deployed as the primary tooling for the so-called Metadata for Machines workshops, where FAIR metadata experts are teamed up with domain-experts to work together to create appropriate FAIR metadata artefacts.

What does all this mean for academic publishers?

Much of what is proposed should be possible to incorporate into current processes and workflows. Publishers already add metadata to whatever they publish. Extending this metadata, and increasing its granularity is unlikely to be a fundamental change for most publishers. It speaks for itself that authors will need to be involved in determining what are the ‘significant assertions’ in the text of their articles, and what is the meaning of any terms used. If an author uses the term NLP, for instance, it should not be for the publisher to decide if it means “neuro-linguistic programming” or “natural language processing.” There are various technologies available that would enable the realization of simple and efficient tools for authors to add semantically unequivocal assertions to their manuscripts, in the way that they currently add keywords (although the meaning of those is often enough quite ambiguous, which must be avoided for key assertions).

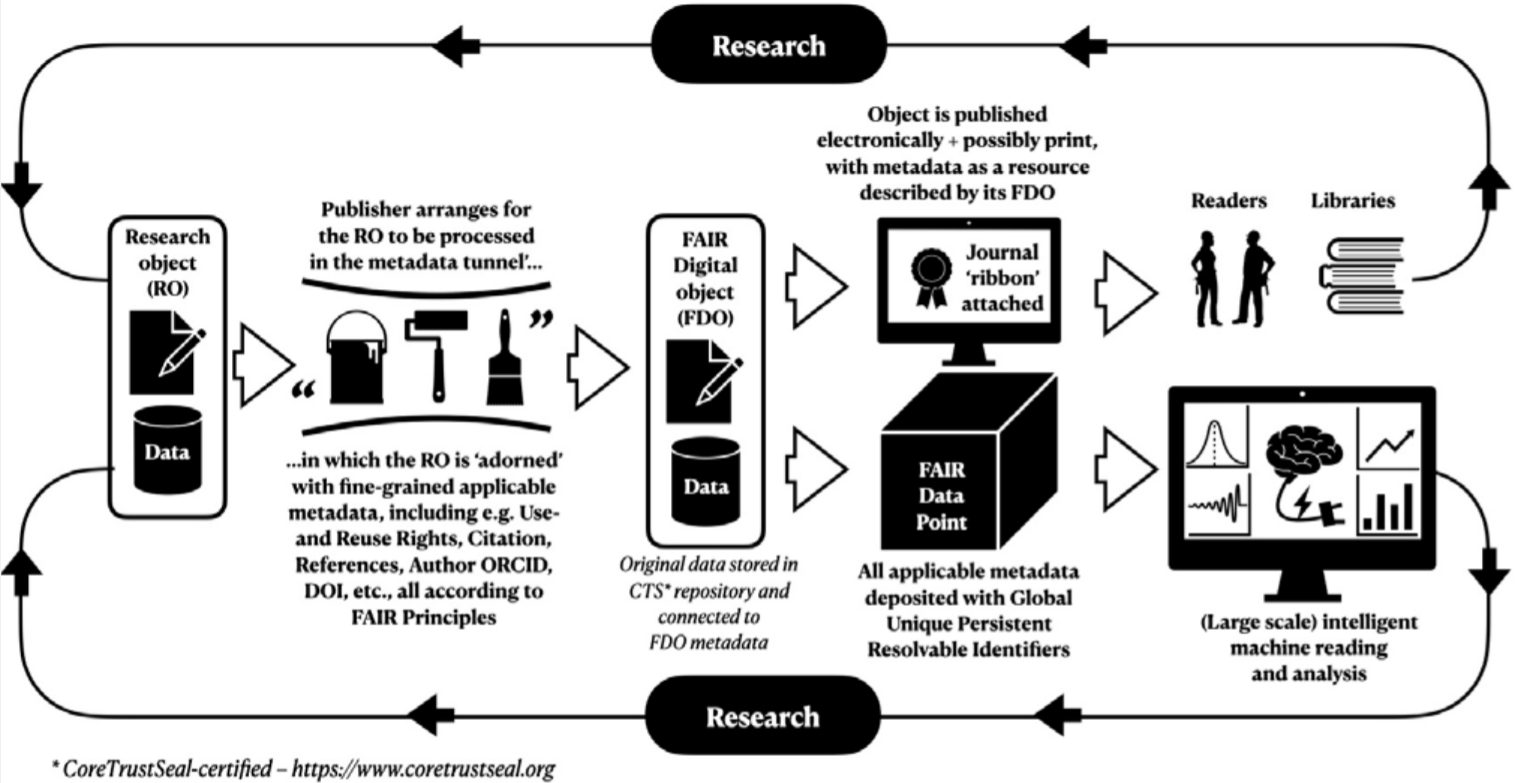

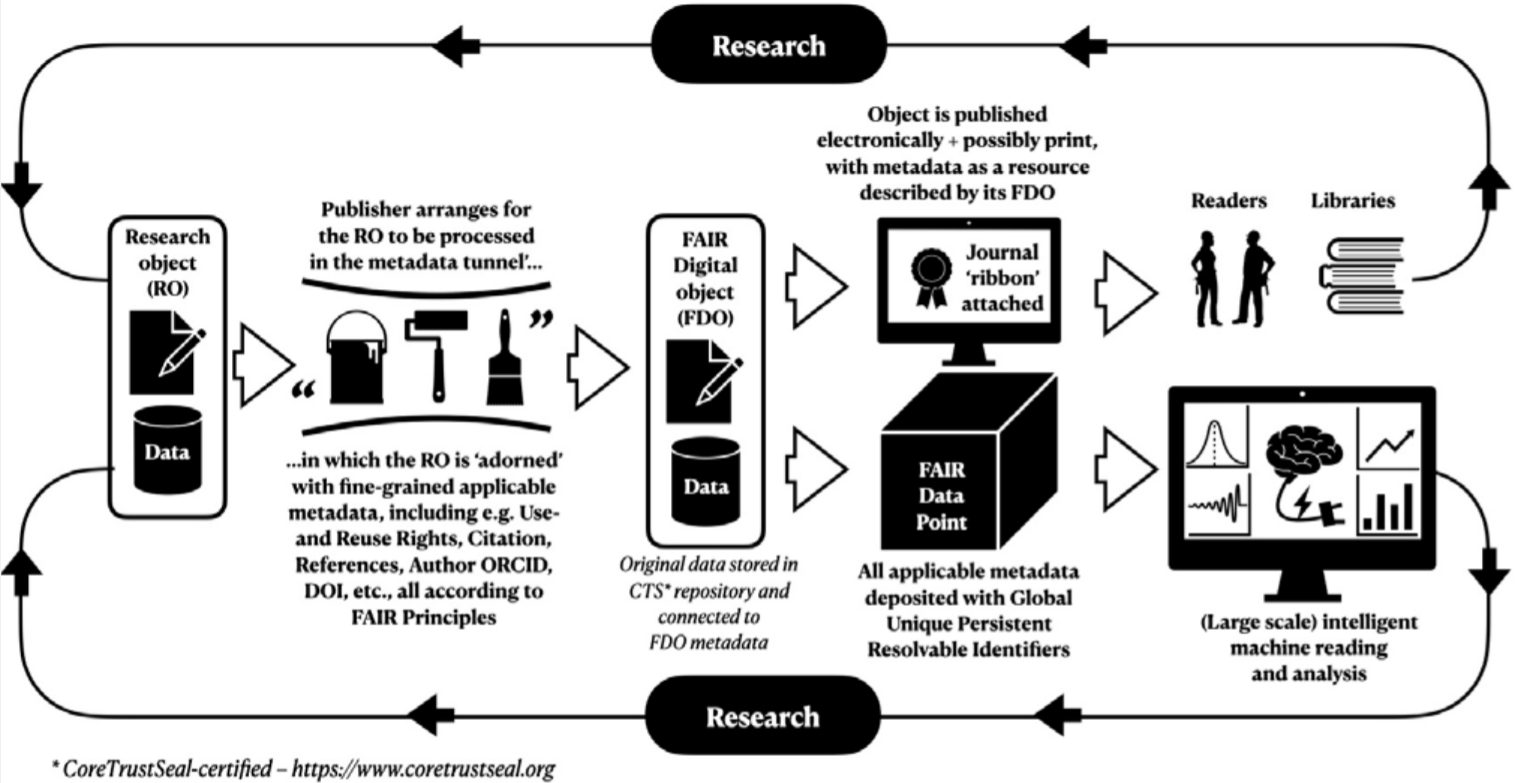

The publishing process should not differ much from the one currently used, as Figure 1 below shows. The main thing is to create (arrange for the creation of) a FAIR “twin” of the original research object as submitted.

Figure 1: The flow of research objects through the publishing process (source: ISU article; credit: Jan Velterop and Erik Schultes)

Proposed manifesto

For an Academic Publishers’ Implementation Network (APIN) to be recognized as a GO FAIR Implementation Network, a “manifesto” is required. Such a manifesto is meant to articulate critical issues that are of generic importance to the objectives of FAIR, and on which the APIN partners have reached consensus. The proposed manifesto is as follows (see Box 1), and at this stage is subject to agreement, modification, and acceptance by the initial APIN partners.

The APIN is envisaged to consist of academic publishing outfits of any stripe, be they commercial ones, society publishers, or preprint platforms. Its main purpose is to develop and promote best practices to “publish for machines” in alignment with the FAIR principles. These best practices would apply to traditional scholarly communication, but with proper addition of machine-readable renditions and components.

All APIN participants commit to comply with the Rules of Engagement of GO FAIR Implementation Networks “Rules of Engagement,” essentially committing to the FAIR Principles and embracing zero tolerance for vendor lock-in formally or otherwise.

Initial Primary Tasks

The next primary tasks will be to coordinate with the partners in the APIN a detailed plan of execution and a roadmap for further development as soon as the process of becoming a GO FAIR Implementation Network has started. Also, to develop rules for authors to stimulate proper FAIR data publishing in trusted repositories with a FAIR data point to support maximum machine Findability, Accessibility and Interoperability for Reuse.